The default way to look at financial “independence” nowadays is to think that means “making a lot of money.” That’s understandable.

But then you see stuff like this:

![{map[alt:60% of millennials earning over $100,000 say they're living paycheck to paycheck. class:titleimg src:/pix/millennial-paycheck.jpg] /home/luke/work/code/lukesmith.info/content/articles/minimizing-liabilities-is-making-it.md <nil> img true 0 {{} {{} 0} {{} {0 0}}} {{} {{} 0} {{} {0 0}}} 374 { 0 0 0} <nil>}](/pix/millennial-paycheck.jpg)

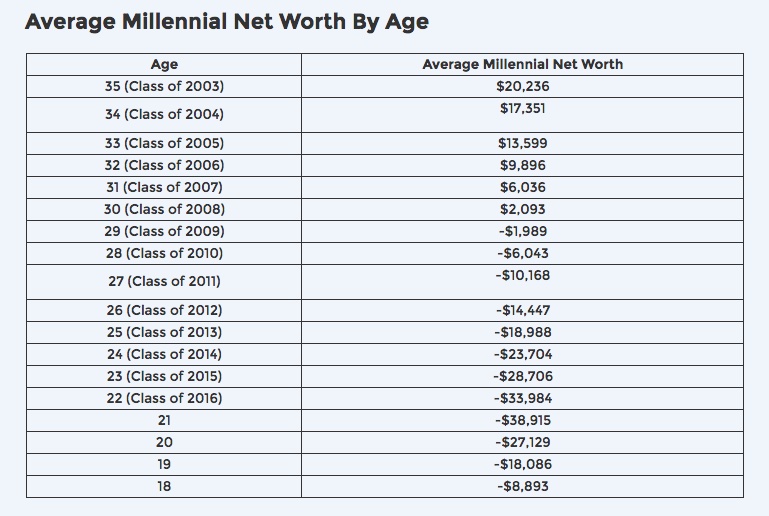

Or this:

The longer you mentally analyze the second picture, the more depressing it will get. Obviously the negative net worth early in life is kids losing around $10,000 a year in value by going to college, but the truly depressing thing is that after that period, their net worth increases only by an average of about $5,000 a year.

That means they might have $5,000 more in the bank or $5,000 paid off of their student loans or $5,000 going to equity in a house, but no combination greater than that.

How does this happen?

How is it that people alive in the period of the highest and most productive technology are working more than Medieval serfs?

Let’s put it in simple terms by defining “making it:”

- Making it:

- Earning or having significantly more money than you spend or owe.

Or in pseudomath:

To increase comfortablity, you can increase your income or decrease your liabilities. This is a simple equation.

By “liabilities” I mean:

- the cost of food you have to eat to live

- the cost of the place you need to live

- the payments for goods and services you actually need (power, or perhaps a car, etc.)

- debts

The problem I would estimate is that people focus all of their time, money and interest on increasing their income and focus quite literally none on decreasing their liabilities, which is actually substantially easier anyway.

In fact, the modern economy, including all the bad advice it gives to people can generally be thought of a system that is desperatly trying to increase everyone’s liabilities within it. Financial libabilities, debt and others, breed even more financial liabilities.

The Lifestory of Basically Everyone Nowadays

Let’s illustrate this with the story of most people you know:

- “I’m going to the best college I can because everyone told me to.”

- “I need to pay off my $40,000+ in student loans, so I need to move to the city and get a good job.”

- “I get paid well, so I need a better car and other stuff to match.”

- “I still have loan debt, car debt and now credit card debt, but now I have a good credit score, so I’ll use all my savings to pay 20% of an expensive house I’ll be paying off for 25 years.”

- “Oh my boss wants me to humiliate myself for sodomy month or get the Coofid vaccine or the Mark of the Beast to keep my job. I have at least a quarter of a mil invested in my life here, so I can’t just leave. Be realistic.”

- “Yeah the economy is really bad and I lost a lot of investments. Either way, this is my career and what I’m trained for. It’d be hard to retrain. I made the right choices, I just got unlucky.”

- “Well, I’m 60 and it’s time for retirement! Now that my body is broken I can start enjoying life!”

- *Dies of seed-oil-induced heart attack.*

It’d be wrong to singularly blame student loans for all of this, but there is a tangible sense in which opening up any new massive monthly liability to the system encourages people to open up more to cover for it.

No one is ever told that this is the inevitable end of increasing liabilities: you need more and more liabilities.

“Which way Millennial?”

Millennials come in two financial categories: around 90% of them are extreme consoomers who cannot not spend every penny of their salaries on subscriptions, plastic toys and coffee and seem to view the fact they get calls from collections agencies as some unpreventable outcome of “capitalism.”

The other 10% are the exact opposite: they are contemplating living in the trunk of their 1990’s Corolla parked in the parking lot of their job site so they can save 97% of their income. When they plan on buying a house or getting married, they are quixotically salivating on how much money they can save on monthly bills.

The Endgame

I will go ahead and say, I consider the ideal not even to be rich, but to not need money to live a comfortable life because you have put yourself in a geographic and behavioral position where you can survive on as little as possible.

Either way, my mindset (as the second type of millennial) has always been “How can I absolutely minimize the amount of money I need to live?”

- “What is the cheapest place to rent?”

- “What is the cheapest-per-calorie real food for me to eat?”

- “What “needs” are not really needs and can I go without?”

The implicit goal was to live on as little as possible: that’s what actually maximizes your life’s freedom. If you can live on less than, say, $500 a month, even working as a part-time wagie, you will be plenty to pay bills, save a significant amount and have lots of free time.

For young single guys in computer science, this is especially ideal, since your hobbey/craft doesn’t cost anything to tinker with.

In my late twenties, right before I bought my house, I was living in a college town with a monthly budget including my rent of around $400 ($300 was rent $100 was basically groceries). Probably went over that $100 most months, but never by much. This is also when I started churning credit cards to make a significant portion of my little expenditure back.

Behavioral Patterns over Life

As you’re saving money to buy/pay off a permanent dwelling place, most important is cultivating permanent behaviors that will reduce your need for money and “the system.”

If you take the “high”-income, high-liability route, you’re going to be establishing wasteful antipatterns your early life and when you need to buckle down and root those out, it will be more difficult because it will be the egotistically trying task of going from showly and “easy” pleasure spending to a Spartan budget.

It’s much easier to have a solid foundation of low spending. I said in that video years ago on getting Trumpbux that all money you earn and spend should be directly weaponized to decrease your reliance on money. Property, tools, plants, skills. These are investments much more substantial than investing in boomer stocks because they lessen your need for money.

Worst Case Scenario

As a passing remark, I’ll add that the other benefit of focusing on minimizing liabilities is that it makes you significantly less reliant on “the system” and more robust in the case of disaster.

“Training” to get a highly specific corporate job is not going to help you in all possible scenarios in the way that simple the simple craftsmanship of someone who fixes their own cars and things.